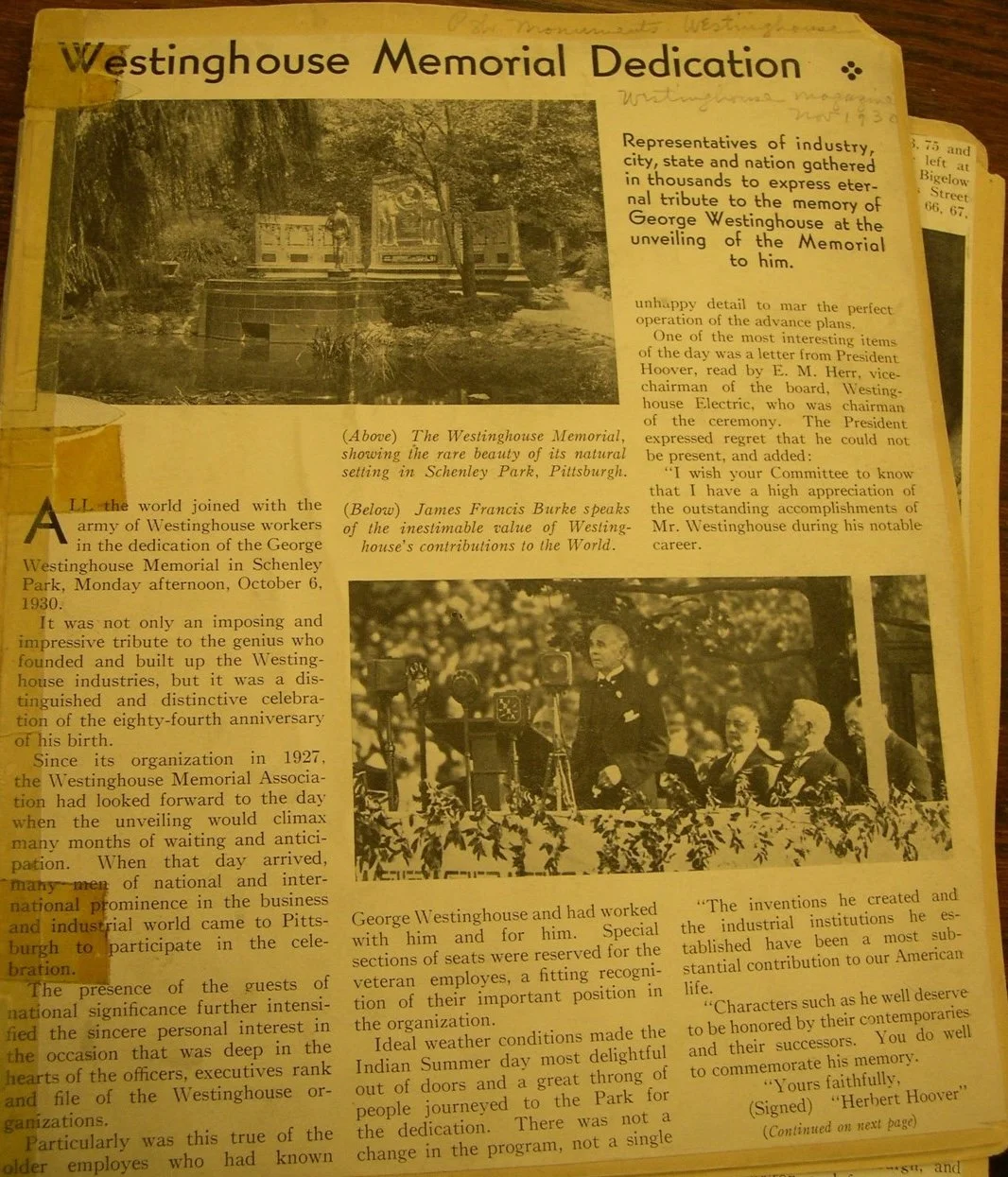

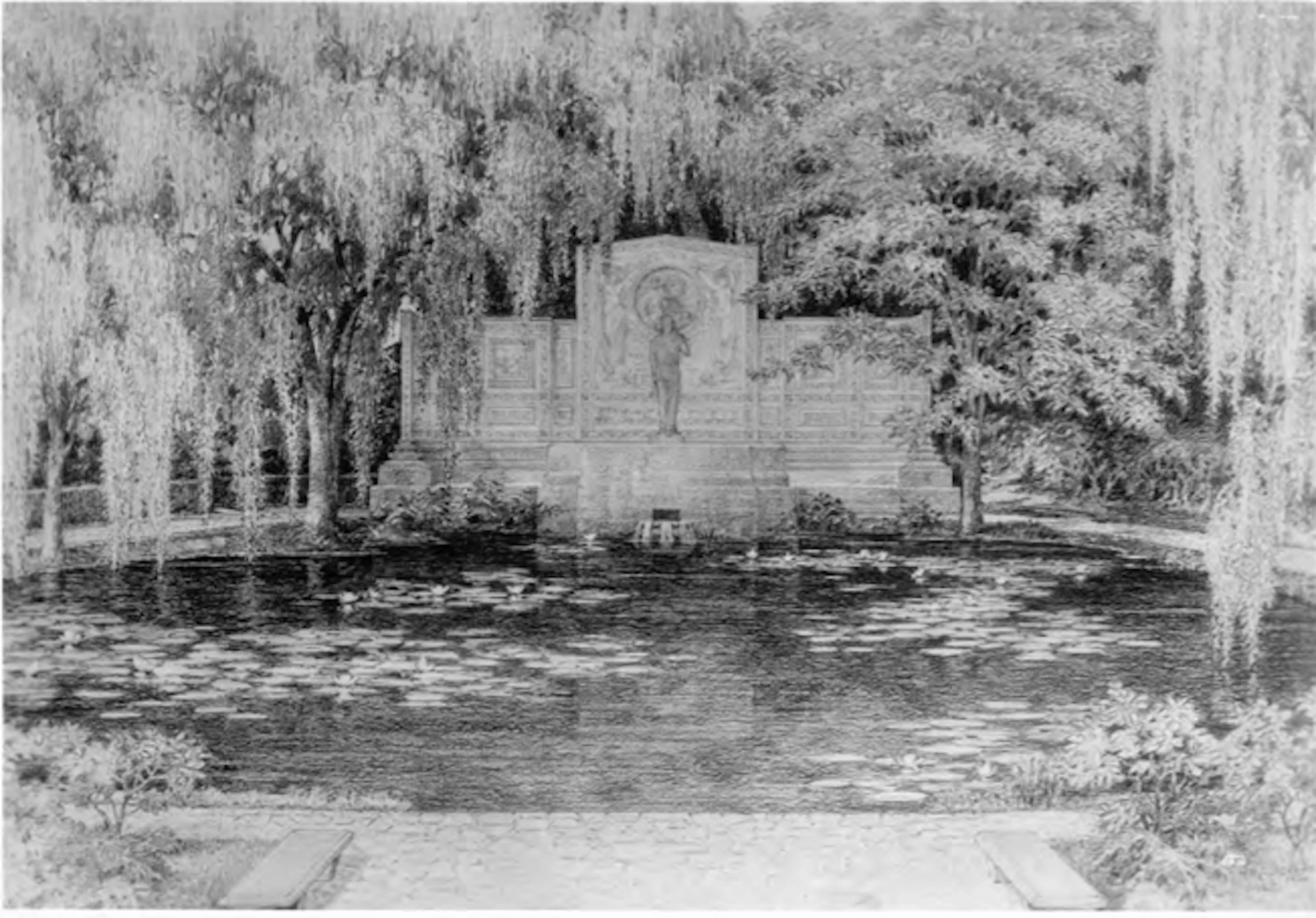

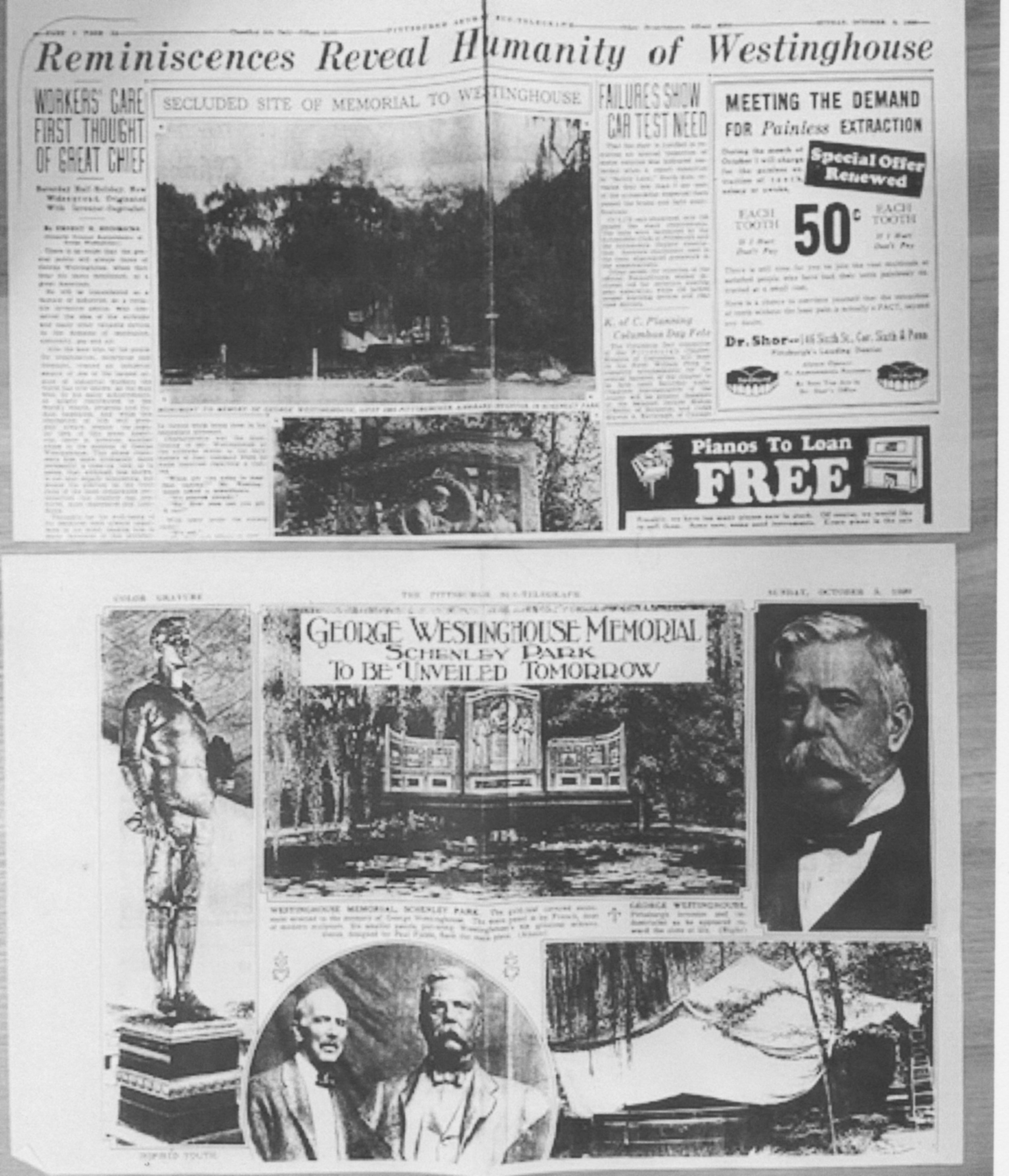

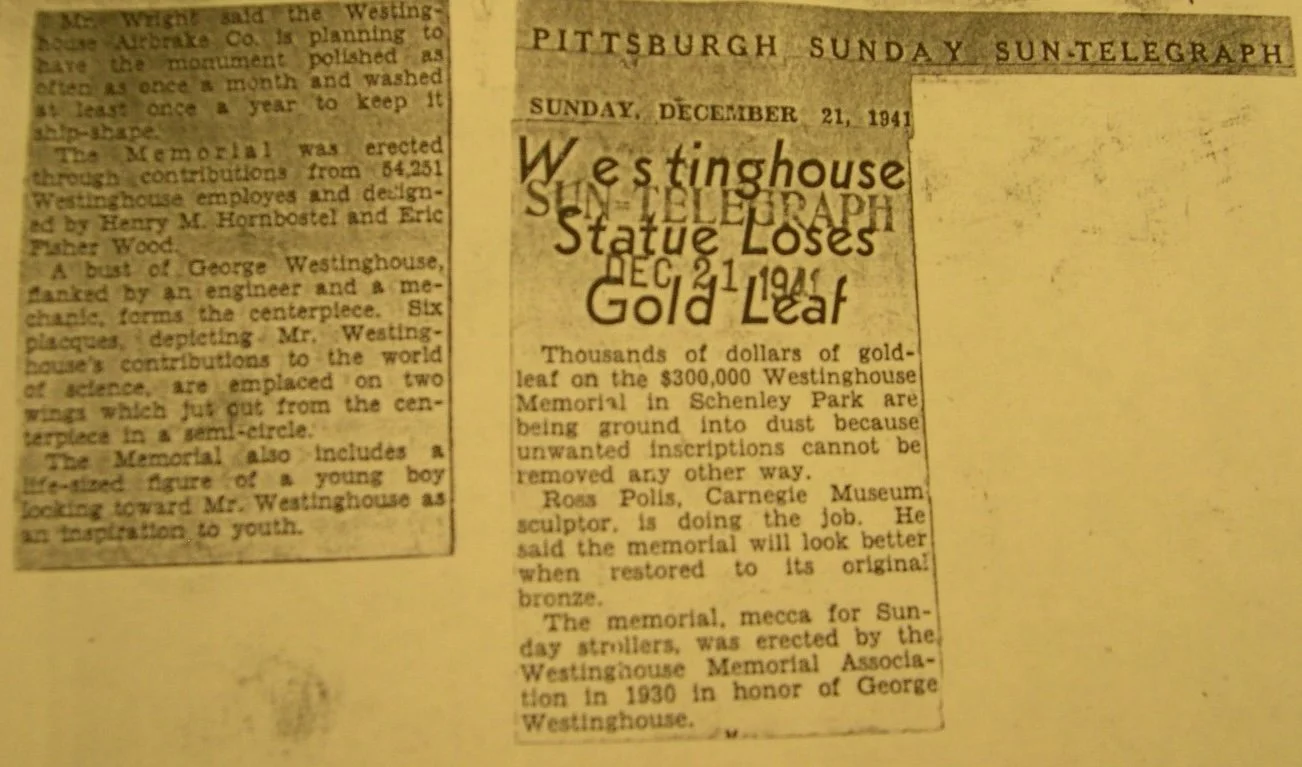

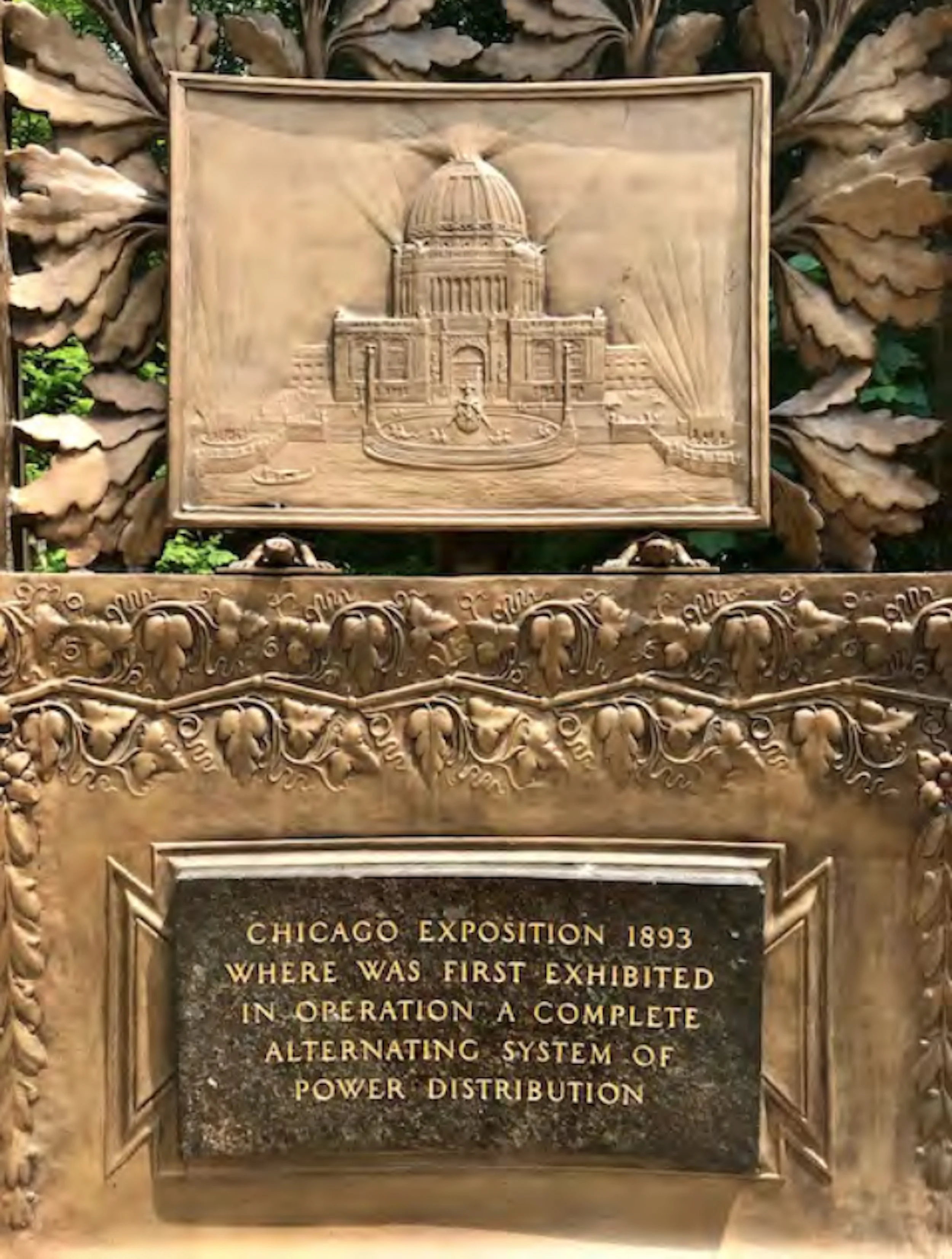

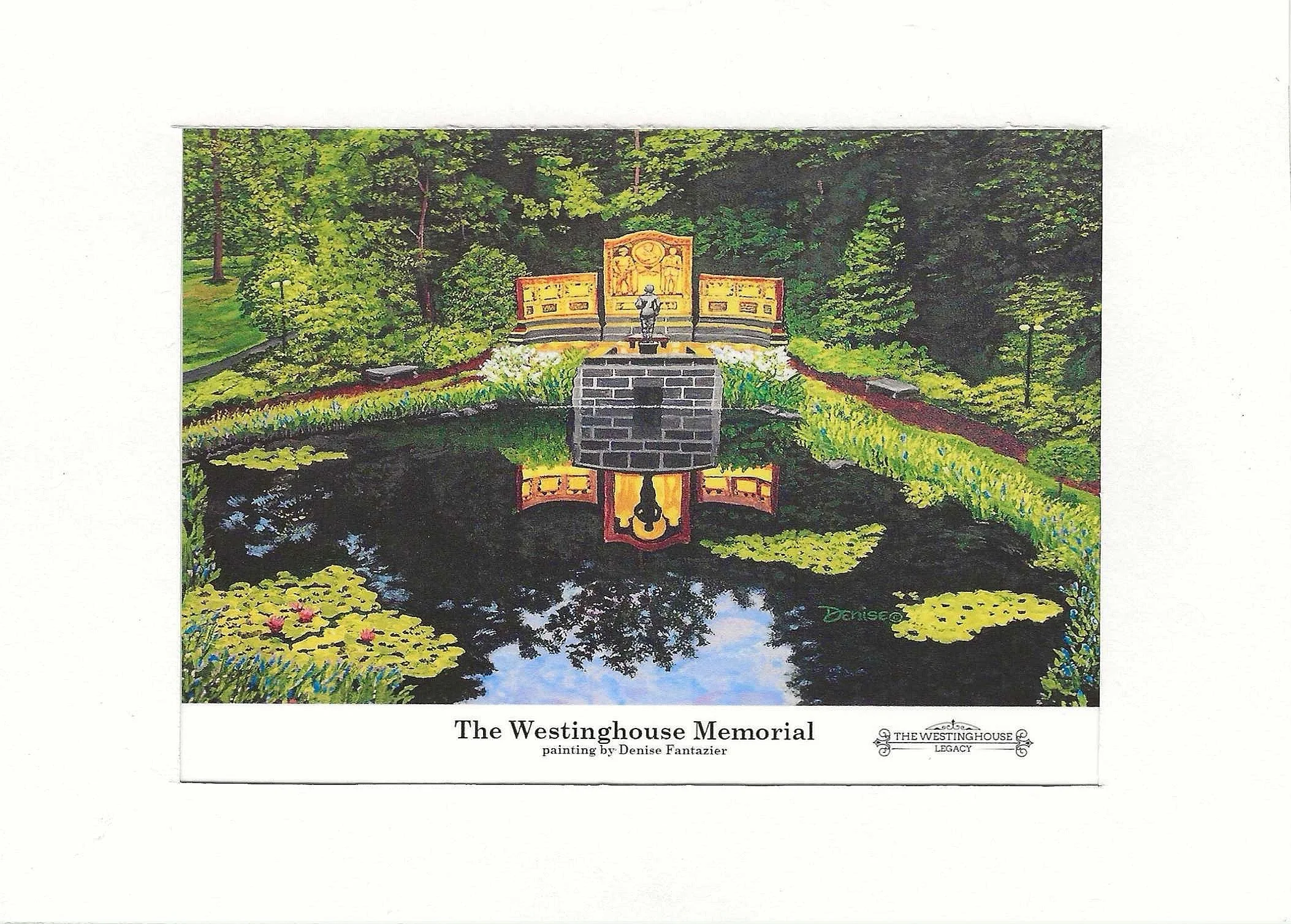

The rear side of the memorial with its dedication

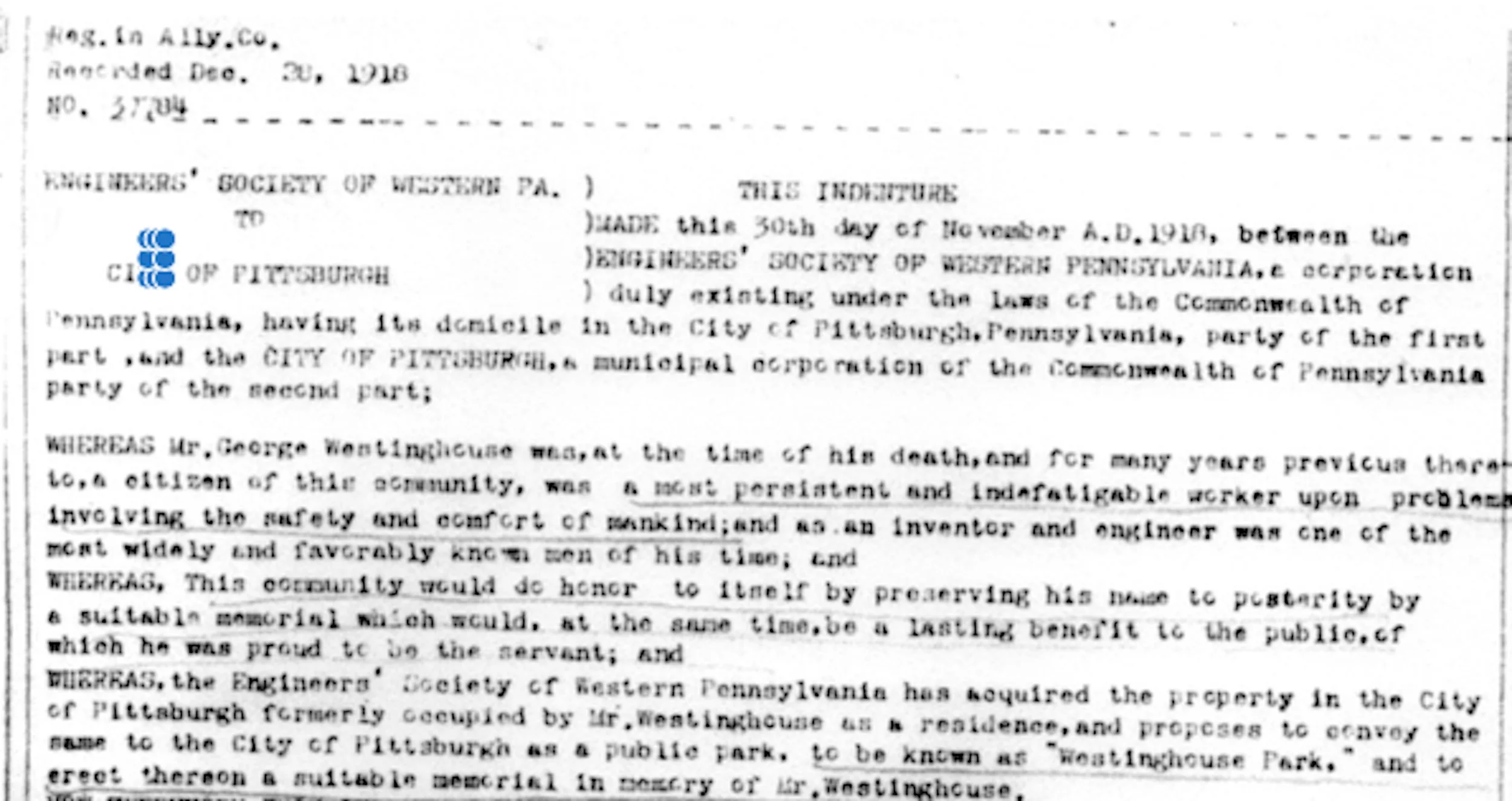

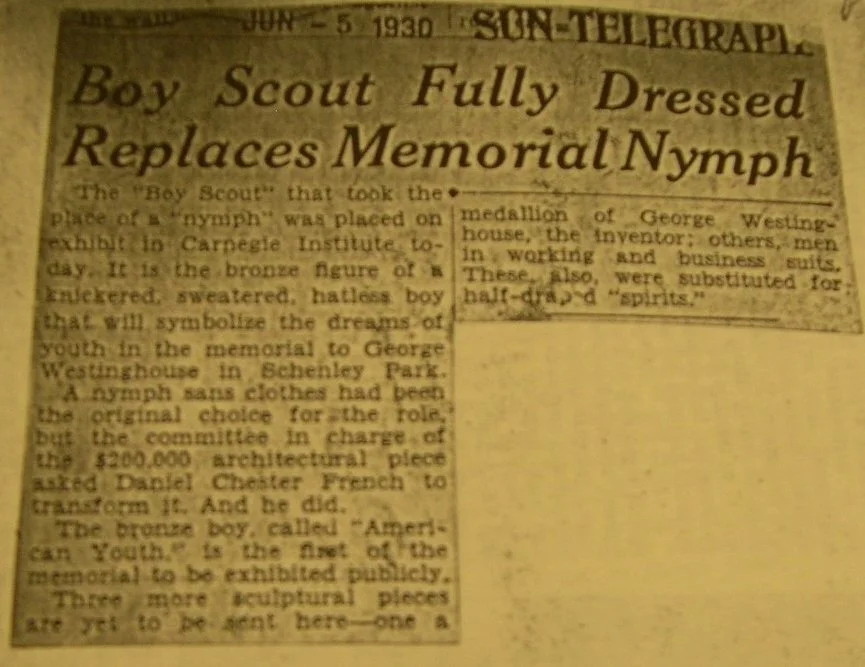

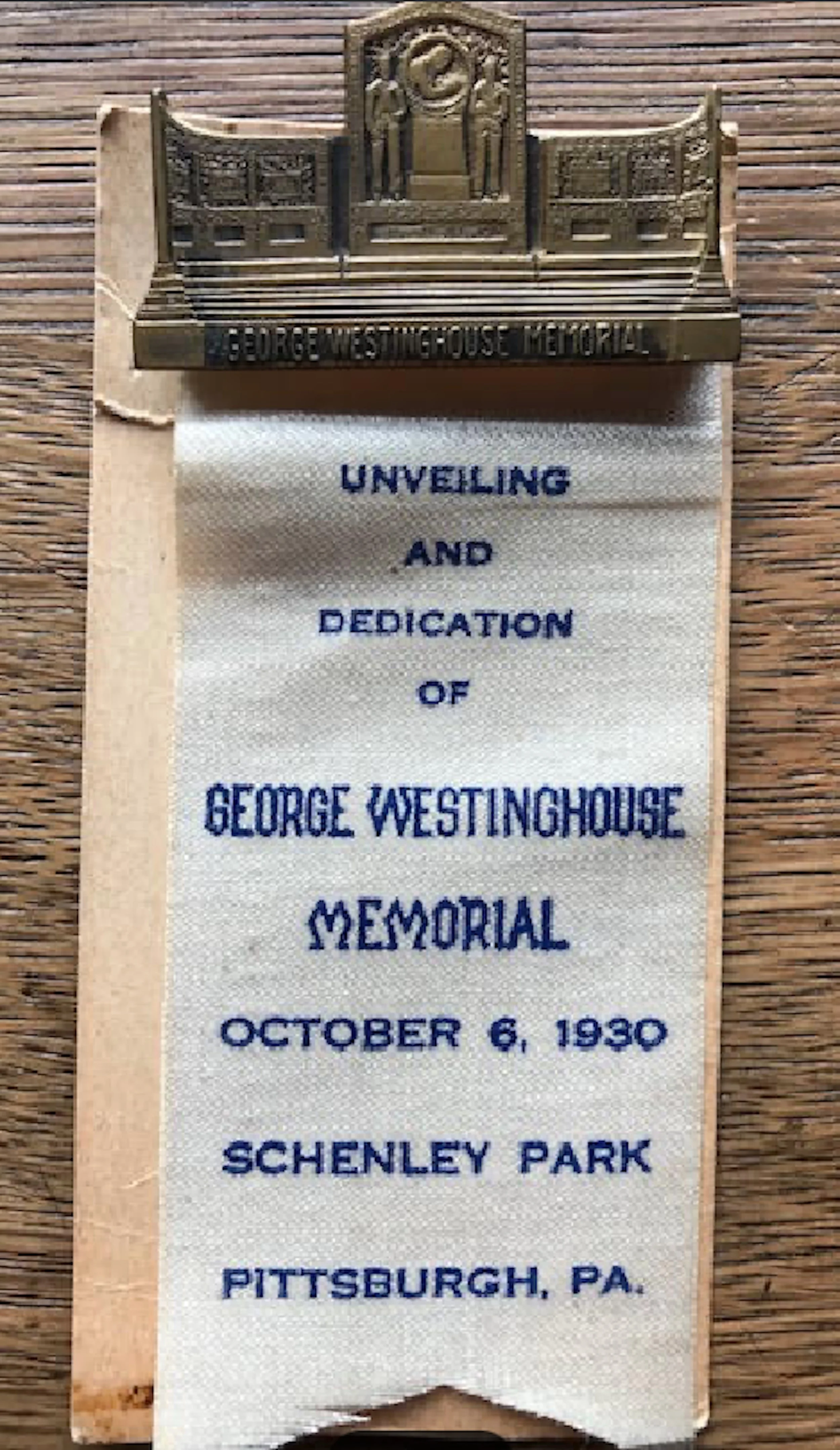

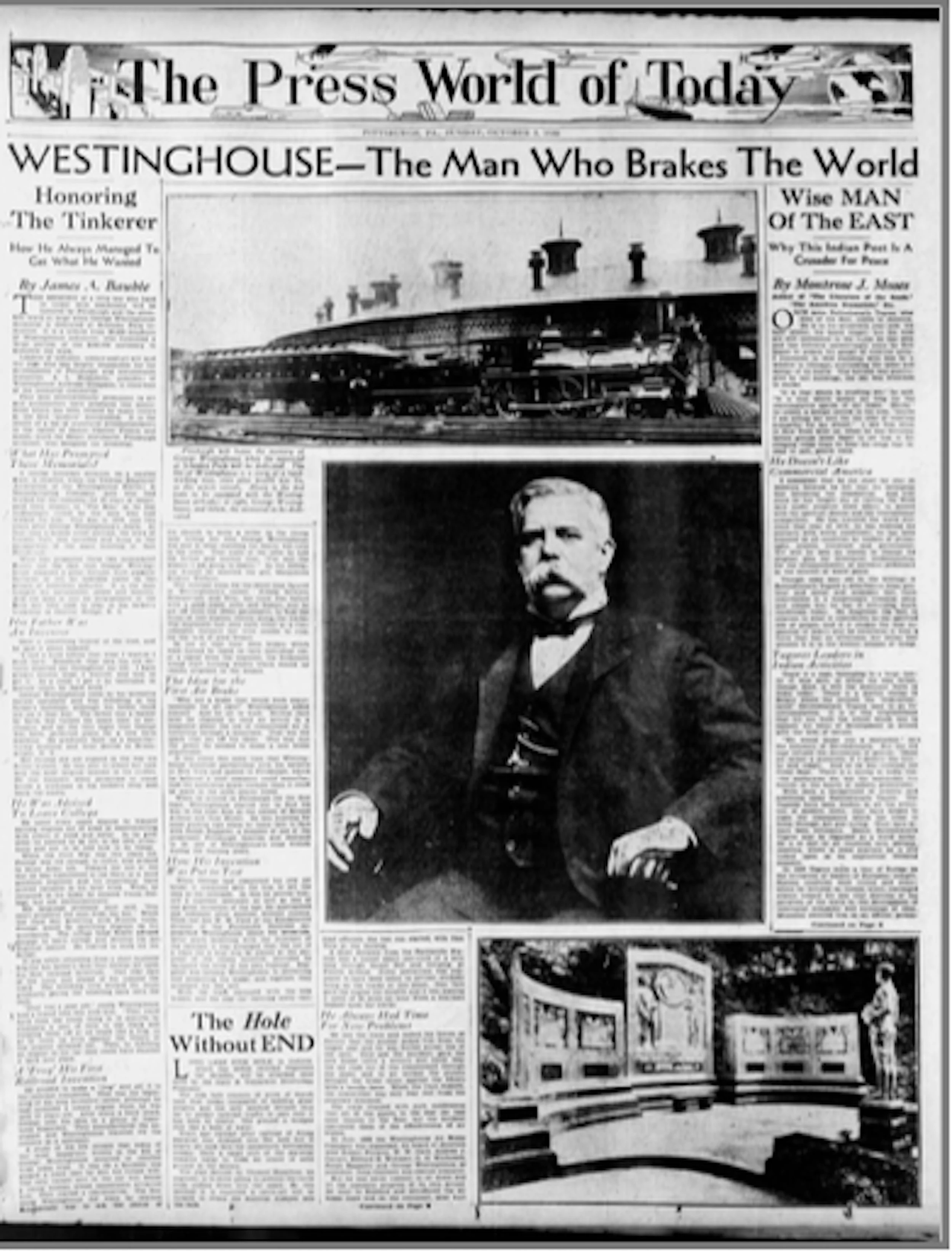

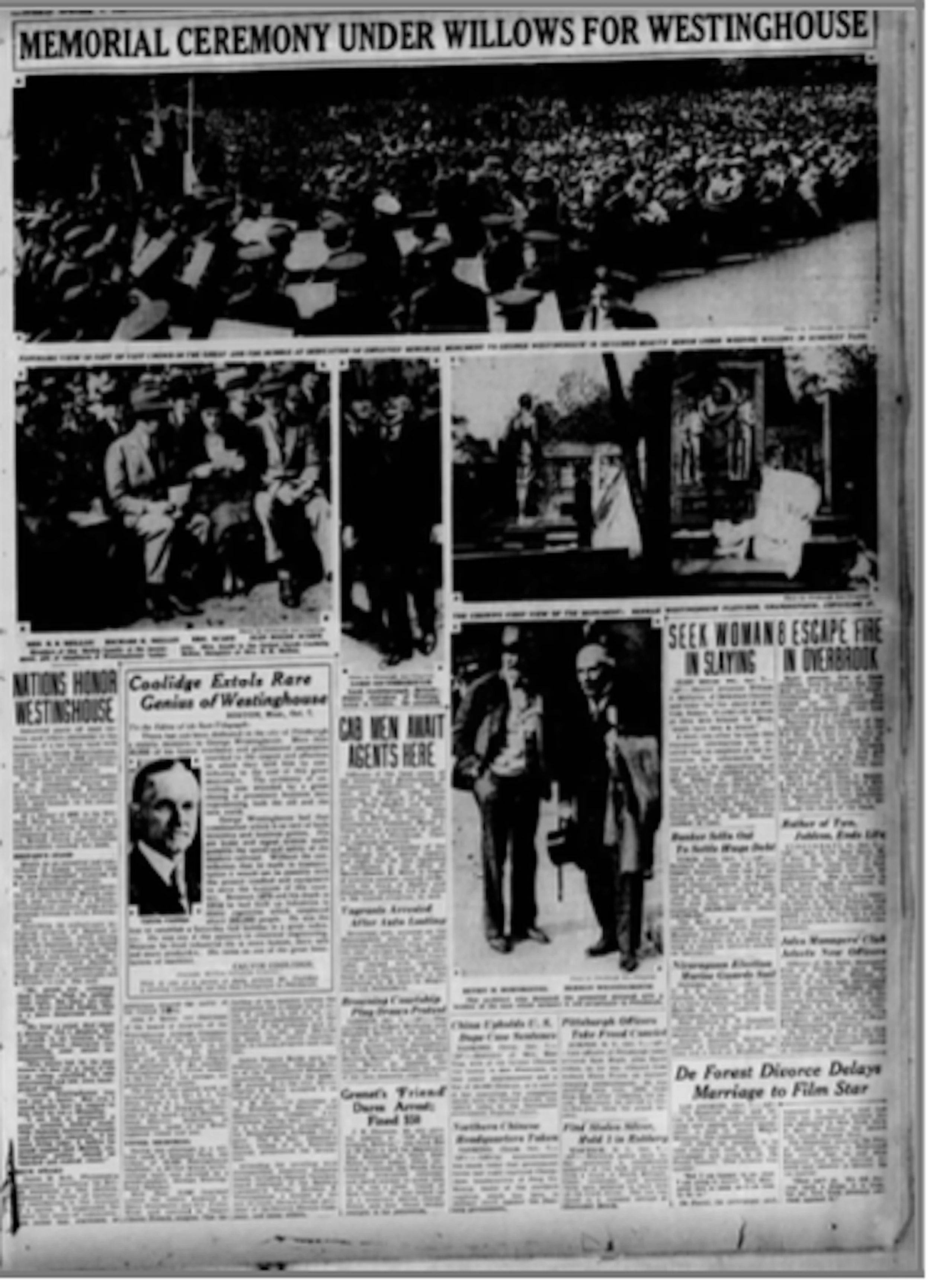

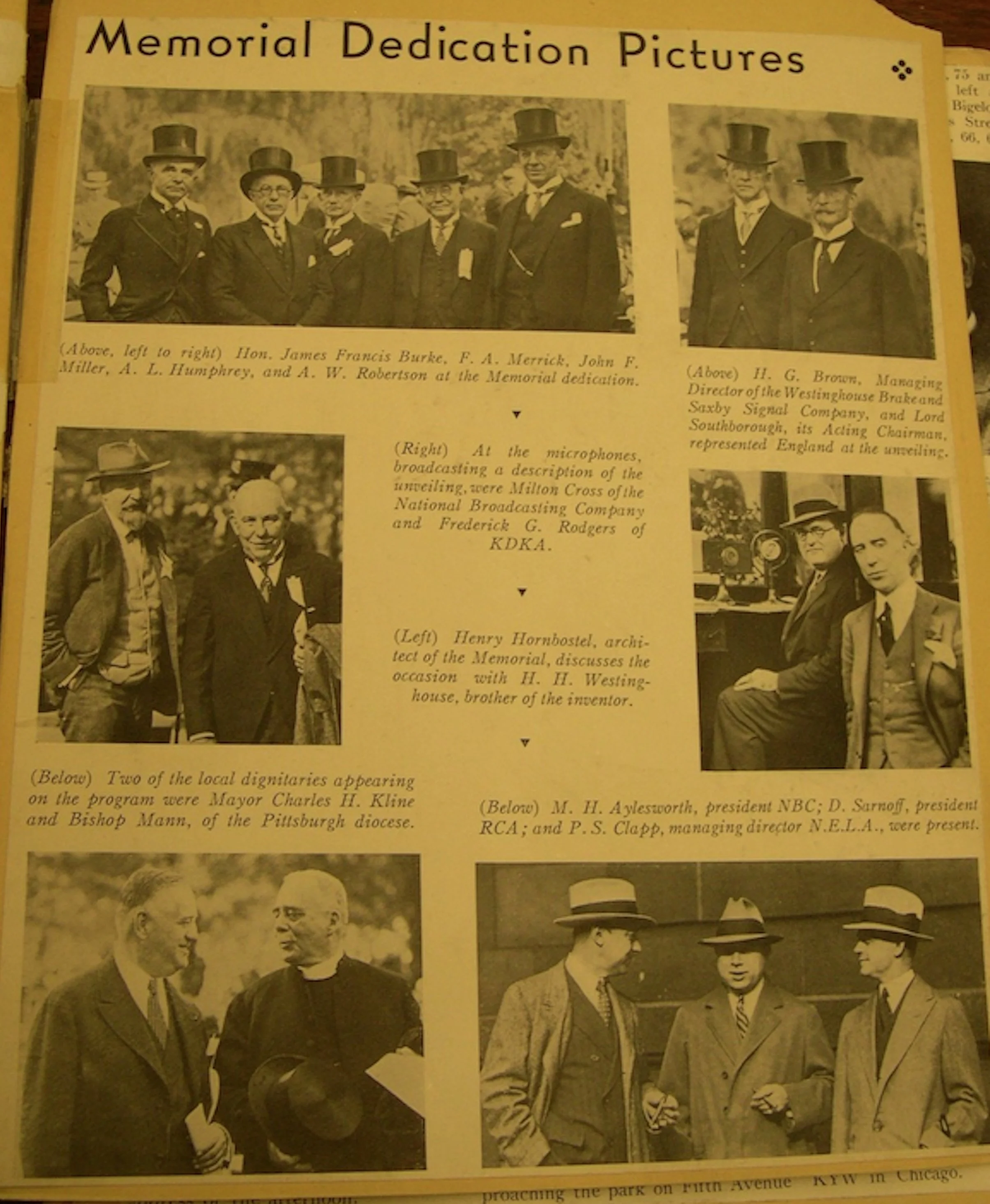

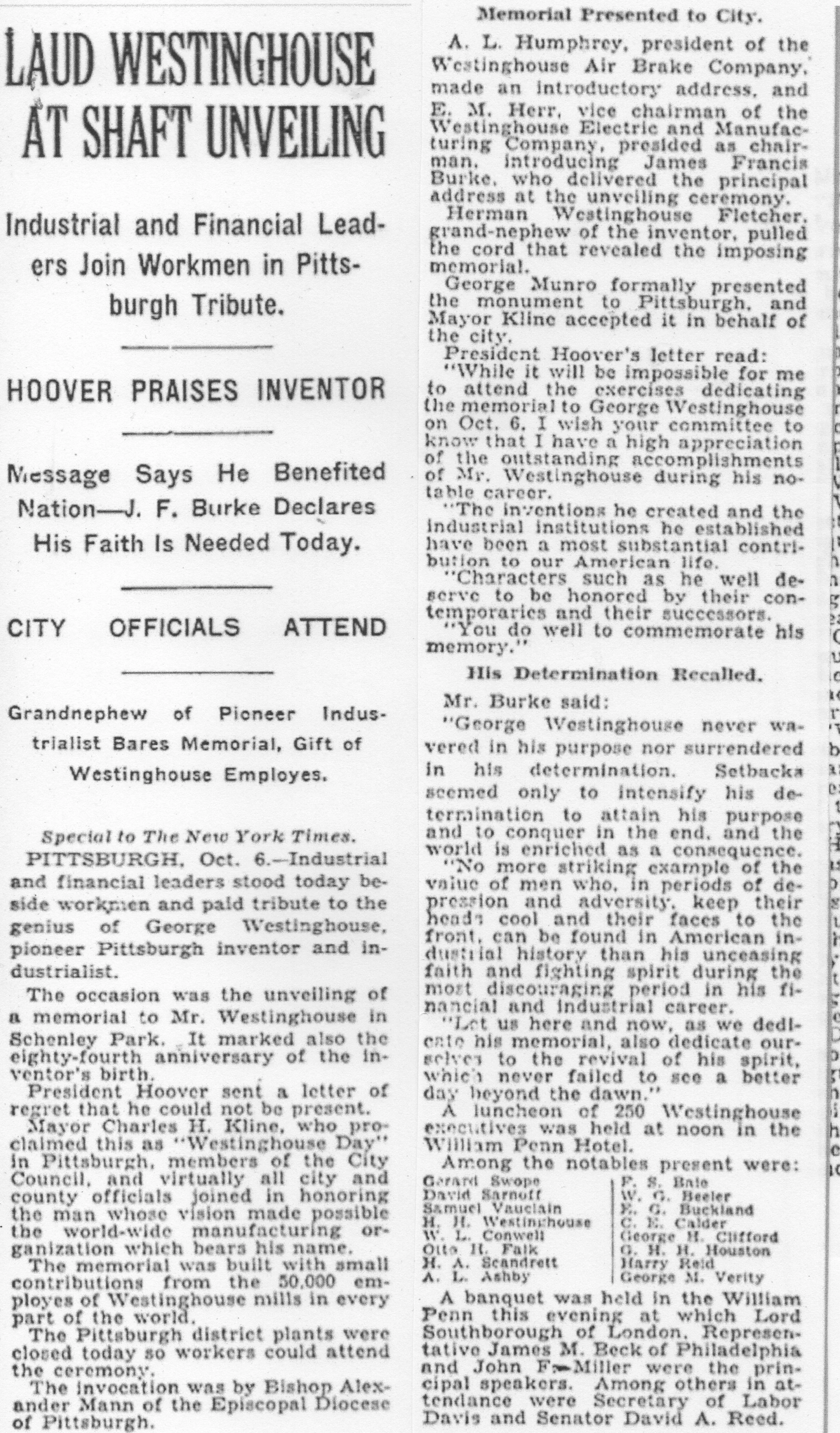

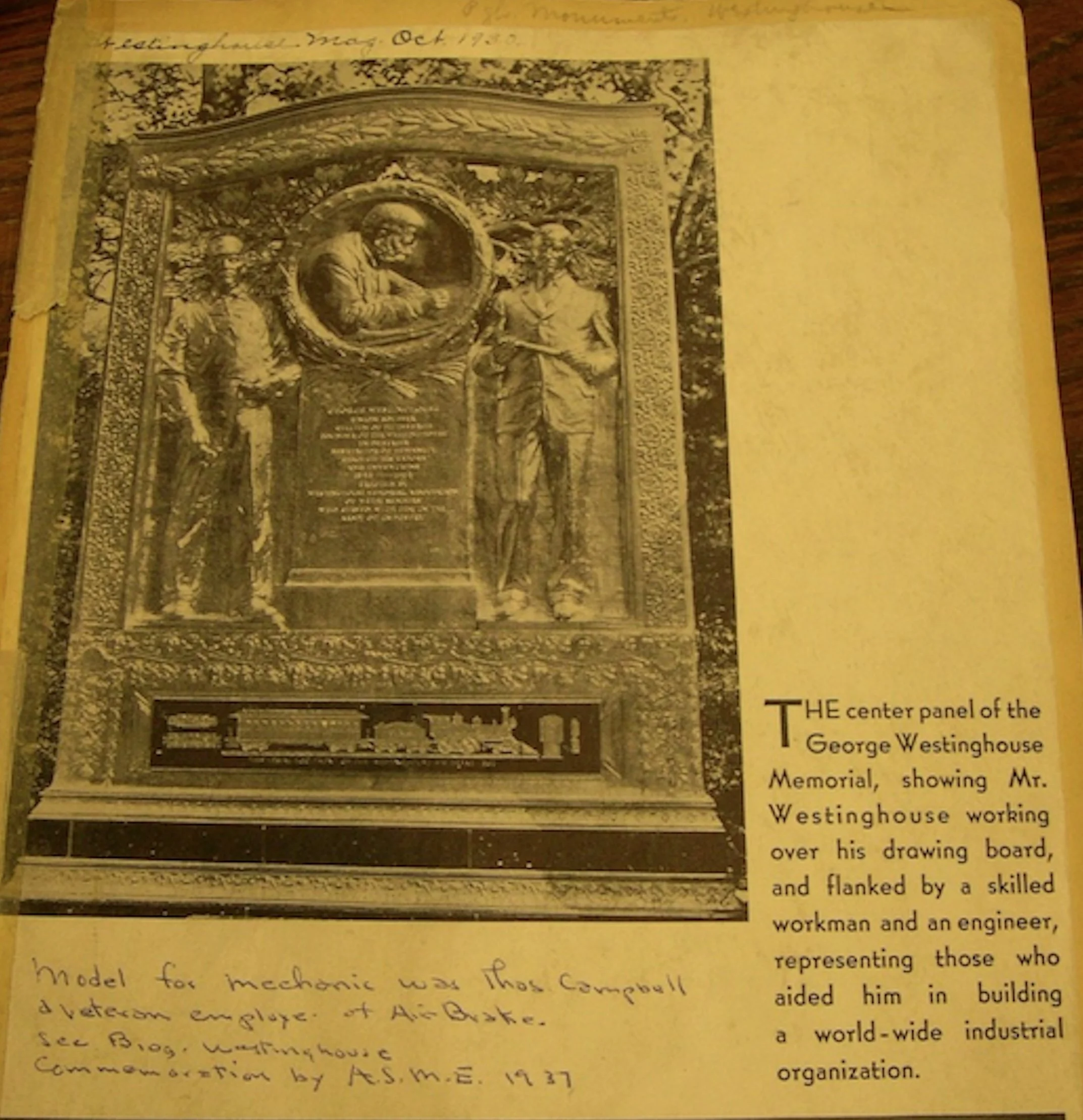

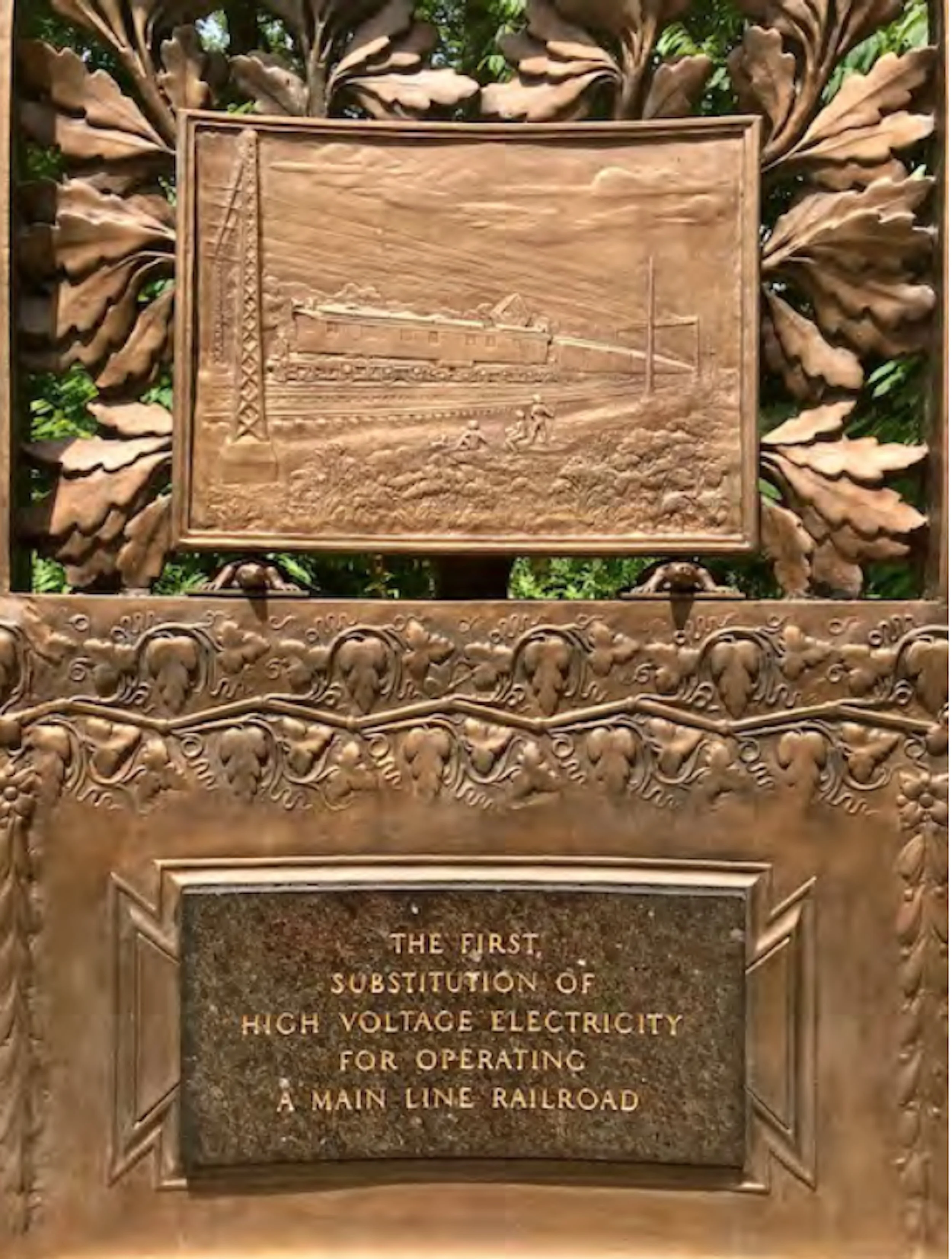

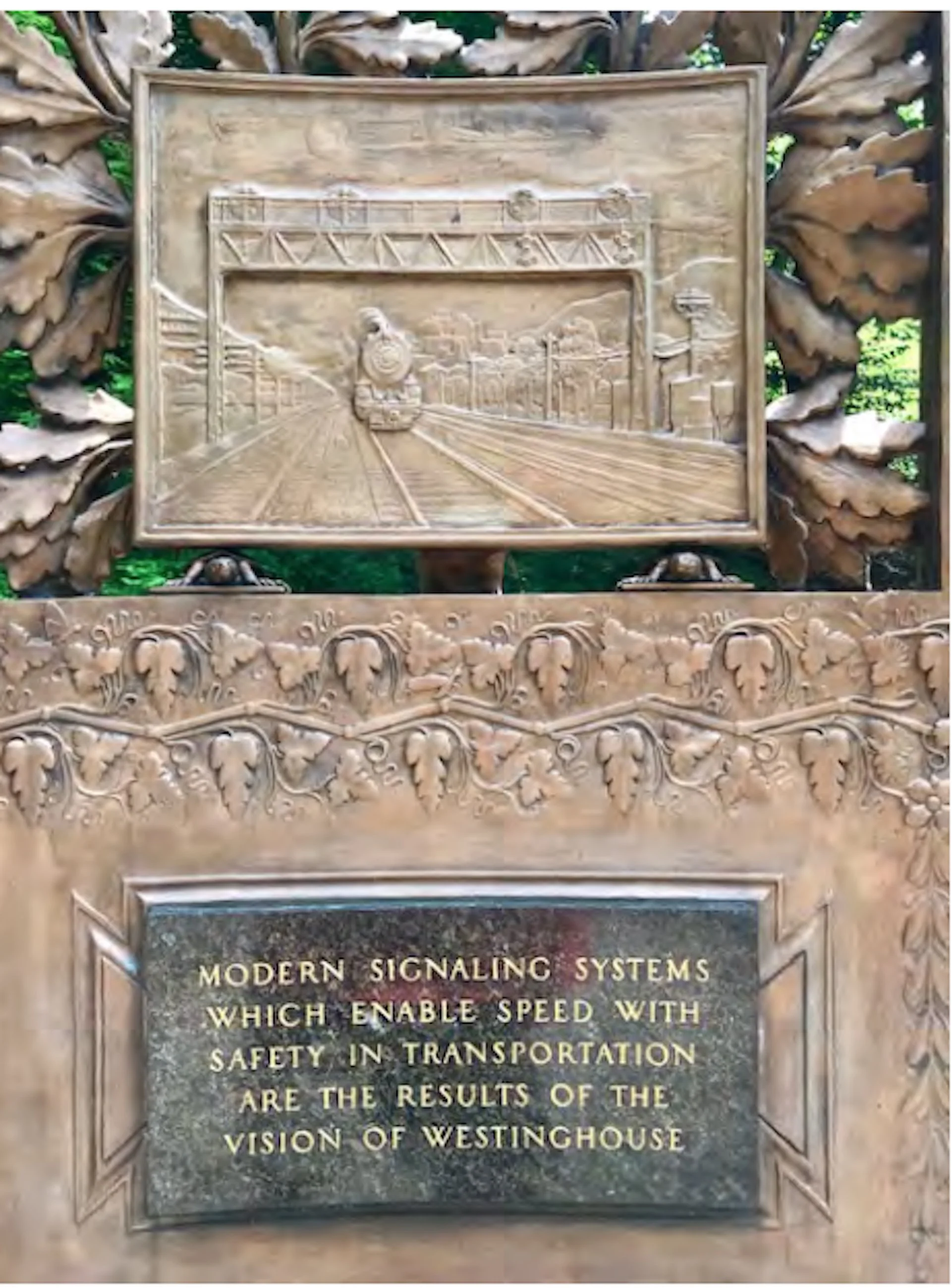

This memorial unveiled October 6, 1930, in honor of George Westinghouse is an enduring testimonial to the esteem, affection, and loyalty of 60,000 employees of the great industrial organizations of which he was the founder. In his later years, rightly called "The Greatest Living Engineer," George Westinghouse accomplished much of first importance to mankind through his ingenuity, persistence, courage, integrity, and leadership. By the invention of the air brake and of automatic signaling devices, he led the world in the development of appliances for the promotion of speed, safety, and economy of transportation. By his early vision of the value the alternating current electric system, he brought about a revolution in the transmission of electric power. His achievements were great, his energy and enthusiasm boundless, and his character beyond reproach; a shining mark for the guidance and encouragement of American youth.